Championship rules 2016/17

This season (2016/17), new ‘Profitability and Sustainability’ rules operate in the Championship; for the first time, clubs will be assessed over 3 seasons (rather than just a single season). This change brings the Championship clubs into alignment with the Premier League – both have ‘Profit and Sustainability’ rules that are now fully aligned. Crucially, this harmonisation of the rules comes with the blessing of the Premier League - so we shouldn’t see any repeat of the stand-offs that arose (and are still ongoing) with QPR and Leicester. Previously, the Premier League bosses refused to help the Football League collect the ‘Fair Play Tax’ fines for clubs that overspent but won promotion – this lack of support significantly undermined the Football League and severely impacted on the effectiveness of the Football League punishments.

There are a number key changes:

- The assessment is carried out in March (rather than December)

- The maximum loss limit is now £13m per Championship season (or £5m a season of the owner does not inject equity to cover losses).

- Losses are assessed over three seasons (rather than just over the single, previous season)

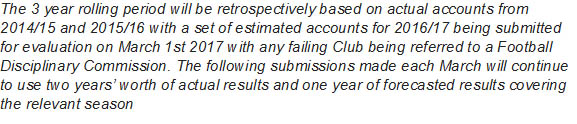

- The assessment of each club’s finances is a combination of a historic assessment (looking at figures for the two previous completed season) and an assessment over the season currently taking place

The last point is particularly significant; in addition to historic account information about past seasons, clubs now have to submit a financial projection for the season that is still taking place. All the information has to be with the Football League by the 1 March. The Football League have confirmed that they are aiming to have any punishments announced before the end of the season.

Rule confirmation text supplied by Football League:

This can be summarised in a table for this season:

Any punishment for breach of the rules will be determined by an independent panel (the ‘Fair Play Panel’).

But what are the potential punishments? Previously the Football League has only been able to either; fine promoted clubs (a fine the Premier League didn’t help them collect), or impose a transfer embargo for historic overspending (which always like a stable-door/horse scenario). With this change, a wide range of punishments are now available. Nothing is off the table; the Football League are now able to impose a points deduction during the current season, or demote a club from an automatic promotion position into the play-offs (or out of the play-offs altogether). Transfer embargoes are also available (with the earliest one potentially applying during the Summer 2017 Transfer window.

Moving from an assessment over one season to an assessment over three seasons has presented some challenges. Interestingly, rather than introduce the changes on a staggered basis, the Football League has introduced the change in one go. The contentious issue here is that for some clubs, a historic ‘rogue’ season which the club had put behind them, suddenly becomes part of the assessment criteria. Where this has happened and where a transfer ban has previously been imposed and subsequently lifted (eg Fulham, Forest, Cardiff), it seems unlikely that the Football League would apply a further punishment if the projections for the current season show the club is currently operating within the £13m maximum loss figure.

Maximum loss limits

Championship clubs will be allowed to lose an average of £13m a season (or £5m if the owner doesn’t inject cash into the club to cover the loss). Hence, a long-standing Championship such as Brighton, is able to lose up to £39m over the three-season assessment period.

Clubs are permitted to exclude some expenditure (Youth development spend, Charitable Community spend, and Women’s Football spend). For a Championship cub this rarely exceeds £500k per season (and is usually less).

Clubs relegated from the Premier League are allowed to make losses of up to £35m in respect of any season spent in the top flight – this should allow clubs to better manage the transition.

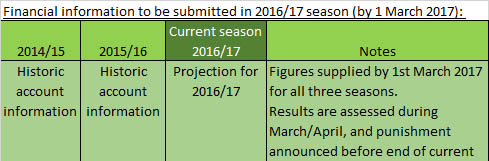

The following table illustrates how the maximum permitted loss for Championship clubs is dependent on the league they were in during the two previous seasons.

Limits for clubs in Championship in 2016/17 season

*Maximum loss is assessed in March/April 2017 based on submission relating to two previous seasons plus projection for 2016/17

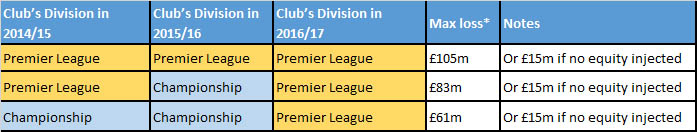

It is important to appreciate that the Premier League will continue to carry out their FFP test ('Profit and Sustainability') for clubs in the top flight – these will work in the same way and take place at the same time as the Championship assessment is carried out, but with the Premier League carrying out their tests.

As with the Championship, the maximum overspend will be determined by the club’s division during the three rolling seasons.

The following table illustrates how the maximum permitted loss for Premier League clubs is dependent on the league they were in during the two previous seasons.

Limits for clubs in Premier League in 2016/17 season

*Maximum loss is assessed in March/April 2017 based on submission relating to two previous seasons plus projection for 2016/17

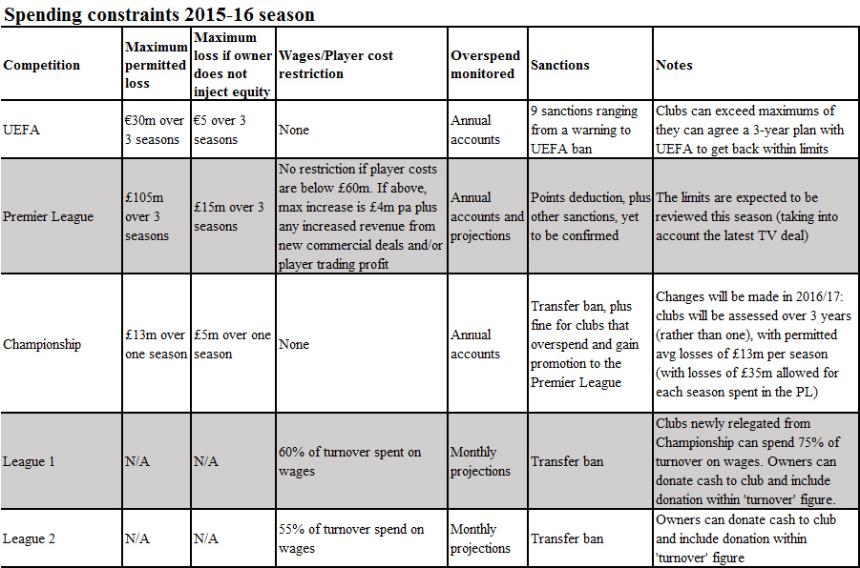

For info, this is how the rules looked at the beginning of 2015/16 season

There were four sets of Financial Fair Play rules in place.(from 2016/17, the Championship and Premier League merged)

- UEFA competitons (for all clubs wishing to take part in the Champions League and Europa League)

- The Premier League (from 2013/14)

- The Championship (with punishments from 2013/14)

- Leagues 1 and 2

Note to editors: the above table (or variants based on it) cannot be produced without permission

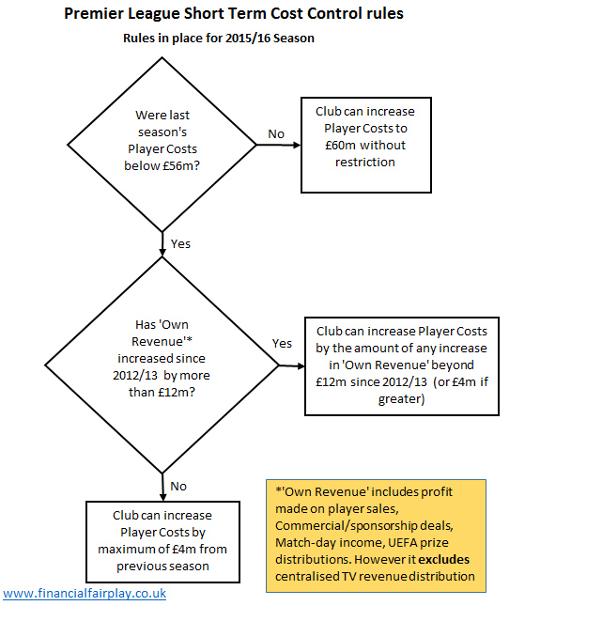

Premier League Short Term Cost Control Rules 2015/2016 season

FFP in the Football League

League 1 and League 2

Anyone interested in the rules in place in League 1 and League 2 should click on the SCMP link at the top of this page.

The Championship

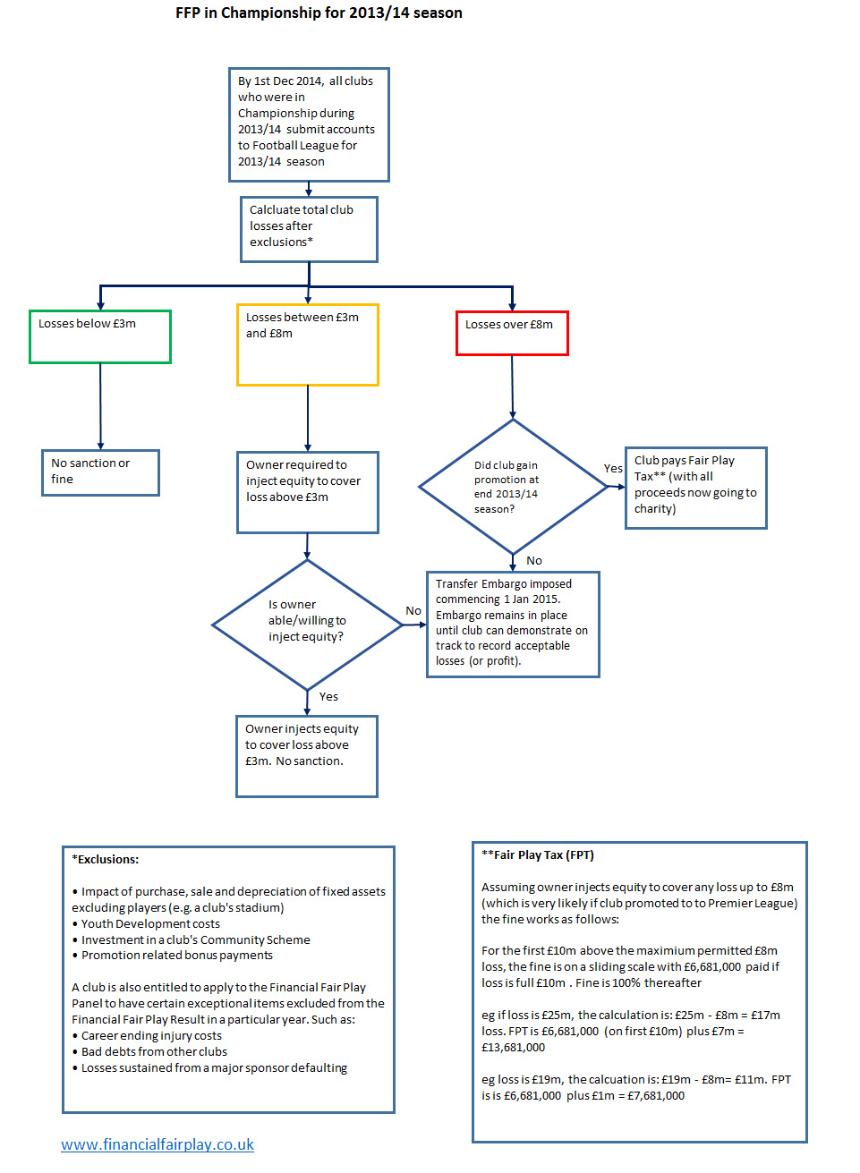

The FFP rules in place in the Championship in the 2013/14 season can be best explained through this graphic. The thresholds have changed since I produced this graphic - the maximum loss for 2015/16 is £13m, (£5m max if the owner does not inject the equity). The rule mechanics and fine structure have not however changed since this graphic. :

Note: The newly relegated clubs must comply with the FFP rules in full. During their first December in the Championship, a newly relegated club does not have to submit their accounts for the previous season (i.e. the accounts relating to the season when they were in the Premier League). However QPR, Reading and Wigan will need to submit their accounts for the 2013/14 season to the Football League (and will be hit with a sanction if their 2013/14 accounts show that losses exceeded the permitted thresholds).

Further Reading: Article I produced for the magazine When Saturday Comes:

|

wsc0001.pdf Size : 1546.53 Kb Type : pdf |

Once you have read the above pdf article and got a good understanding of the concepts of FFP in the Championship/Leagues 1 & 2, you will probably want to go to the Football League web page dedicated to the FFP rules.

UEFA FFP rules documents

If you want to understand the UEFA rules I would recommend you view the my video and article 'Understanding Financial Fair Play' on this page. To be an expert on the subject, you might also want to download and read the full UEFA document, but it is a really tough read! You will need several hours to plough through this document and you might need some basic accounting knowledge. UEFA have issued a 2012 version of the rules:

http://www.uefa.com/MultimediaFiles/Download/Tech/uefaorg/General/01/80/54/10/1805410_DOWNLOAD.pdf

However UEFA have also issued a much clearer document to explain the rules - the attached document was produced for journalists to help them understand FFP:

|

FFP Press Kit EN_FINAL_en _1_.pdf Size : 505.653 Kb Type : pdf |

Quick understanding UEFA's FFP approach

If you want to quickly understand how UEFA's Financial Fair Play rules work (in respect of the Break-Even requirements), the best place to start is with this six-minute video:Understanding Financial Fair Play

Most people use the term 'Financial Fair Play' (FFP) to refer to UEFA's requirement for clubs to balance their books. However the UEFA FFP rules are actually 90 pages long and cover much more than the need to 'Break Even For example, they specify that clubs keep up-to-date with their taxes, their transfer fees and pay player wages on time. Although clubs have been punished under the FFP banner for having 'overdue payables' (Malaga have been banned from UEFA competition next year for falling behind on their tax and wages), the main concern for Premier League clubs is the Break Even requirement. For information on the what else is included in FFP (other than Break Even), you should read this article.

Before we look at the Break Even requirements, I should point out that UEFA's FFP rules only apply to clubs who wish to compete in the Champions League or the Europa League. Clubs have to apply to UEFA to take part and will only get a license if they meet the FFP rules.

Clubs need to apply well in advance and due to the timing of the application process, all Premier League teams will routinely apply midway through the season (for entry into the competitions that start in August/September in the next season). So, although there are no specific Break Even rules in the Premier League (at the moment), in practice, all clubs will strive to comply with UEFA's rules and will usually all apply for a licence (only one Premier League club, believed to be Blackburn, didn't apply last season). UEFA has been keen to give clubs every chance to comply with the Break Even element of the FFP rules; consequently the financial thresholds for passing the test have been phased-in. However the phasing-in of the targets has made the rules rather complicated to understand. There are 5 main reasons why the rules cause confusion:

• Clubs can make a loss and still pass the Break Even test

• The Break Even target thresholds change from season to season

• UEFA asses Break Even over more than just one season

• Certain expenditure can be excluded from the Break Even test

• The permitted Break Even thresholds are in Euros

Monitoring Periods

UEFA believe that it would be unfair to asses a club's Break Even results over just one season and has therefore introduced the concept of Monitoring Periods. Initially clubs will be assessed over two seasons (2011/12 and 2012/13) combined to see if they have made an acceptable level of loss. All other Monitoring Periods other than the first one cover three seasons - the reason for this will become clear when we look at the permitted levels of loss that clubs are able to make during each Monitoring Period.

Permitted level of loss

UEFA appreciate that it would be unfair to fail clubs who make a small loss; consequently they have introduced a concept called the 'permitted Break-Even deficit'. As a result, clubs can make a loss up to a certain level but if they go over the permitted thresholds, they will fail the FFP Break Even test. UEFA understand that because players are often on long contracts and clubs cannot reduce their spending quickly. For this reason the permitted Break Even deficit is set at a fairly high level (€45m) for the first Monitoring Period, and is then reduced in future Periods. The permitted loss falls to €30m for the three year period that covers 2013/14, 2014/15, 2015/16 (that works out to an average loss of €10m or £8m a season).

We should now look at a table to show how the Monitoring Periods work:

There are a few things to point out in the above table.

1. Losses over €5m

UEFA are keen to ensure that clubs don't go deeper and deeper into debt so insist that any clubs losses over €5m during a single Monitoring Period are fully funded by their owner. In practice this means that clubs can only lose up to the maximum €45m during the first Monitoring Period if their owner is able and willing to put their hand in their pocket for any loss over €5m and, in UEFA's terminology, 'convert the loss to equity'. But what does this term mean and what are the implications? Let's use an example of a club losing €30m during the first Monitoring Period. We can see that the club passes the Break-Even test (as the loss is below the €45 threshold). However the €30m loss is above the €5m figure and the owner will need to take some action. In this example the club will create additional shares which the owner will have to buy for €25m (the difference between €30m and €5m). The Club will gain €25m in cash (ensuring the club's overdraft/debt doesn't increase) and the owner will be out of pocket by €25. However, the owner will now hold a potentially worthless paper share certificate. The problem for the owner is that they may never get their €25m back again they might possibly get it back if they sold the club, or if the club makes a profit in future years and he gets paid a dividend). This scenario might not trouble Abramovich or Sheikh Mansour but is the irksome prospect facing the owners of clubs such as Newcastle, Sunderland and Aston Villa.

2. Permitted Exclusions

I should also point out that the level of loss that a club reports in their financial accounts will not be the same figure as is used in the Break Even calculations. This is because UEFA have allowed clubs to exclude certain expenditure from the calculations. UEFA are keen to develop the game and don't want the FFP rules to constrain clubs from investing and developing - without any exclusions a club building a new stadium or new stand would be hit by an FFP penalty (the cost of the development would mean the club reported a large financial loss). Clubs can therefore exclude infrastructure development costs and youth development/community development costs. Manchester City announced that they should be able to exclude around £10m a year as a result of the youth/community exclusion.

There is one other exclusion that causes most confusion amongst journalists and fans; clubs are able to exclude certain wages for their long-standing players. By way of background; when the rules were first proposed, some clubs complained that they were already committed to paying high wage bills for some players on existing contracts and that they could fail the Break Even test as a result. UEFA therefore introduced an appendix to the rules which allows clubs who have failed the Break Even test to run the test again, but this time deduct the wages paid to players on pre-June 2010 contracts. However clubs can only deduct the wages paid to their long-standing players during one season (2011/12) and can only use the exclusion if they can show their Break Even deficit is reducing each year. Chelsea, for example, will probably find that they are not able to deduct the wages paid to Terry, Lampard, Drogba etc during 2011/12. This is because club losses are likely to increase in 2012/13 (they won the Champions League in 2011/12 and are likely to see their UEFA receipts and commercial income reduced in 2012/13).

3. Transfer Fees

An important part of the rules relates to the way that player transfers have to be accounted for. Although a club will often pay a transfer fee to another club immediately, from a Break Even perspective the financial cost of acquiring a player has to be written-off over the duration of the contract. We need an example: let's assume Torres was signed for £50m on a 5 year contract and that Chelsea paid Liverpool £50m via an immediate bank transfer. As far as the Profit & Loss section of accounts is concerned (and the Break Even test), Torres' purchase price would be depreciated (or amortised) evenly over the 5 years of the contract. So, during the first 12 months, only £10m would be incurred as a cost in the accounts and Torres would end the year with a 'book value' of £40m. After 5 years, Torres' contract would have ended and he would be free to leave the club (he would also have a book value of zero). If the club sells Torres part way-through the contract, the club the difference between the amount they receive for the player and the book value at the date of the sale is accounted for immediately in the accounts (and the Break Even test) as a 'loss/profit on player trading'. This is important as it explains how a club can sell a player for below the original purchase price and still record a profit in the accounts during the year of sale. If Liverpool sell Andy Carroll for anything above £18m in the summer, they will record the difference as a profit on player sales during 2013/14. If we assume that Falcao comes to Chelsea for £50m on a 5 year deal in the summer, the club's P&L account for the year will only include £10m as an expense (under the heading 'amortisation'). The club will also, of course, have to include the player wages as an expense in the Profit & Loss account. If you want to know more about 'amortisation', see the video at the foot of this page.

4. Fair Value

UEFA are aware that owners of clubs could look to inflate a club’s profitability by injecting funds into clubs via artificially inflated commercial deals. Paris St-Germain recently announced a huge sponsorship deal via a body that is connected to the club owners. For this reason UEFA FFP rules require any transaction from a ‘related part’ (i.e. a company or body connected to the club owners) to be assessed to ensure it was a genuine transaction at a ‘fair value’. UEFA has the power to adjust any artificial ‘mates rates’ deals and apply a lower value to the Break Even calculation. This assessment will be carried out by the CFCB panel (see below).

The first Test and UEFA punishments

UEFA has set up an independent panel (Club Financial Control Board – CFCB) to assess if clubs have broken the FFP rules (including the Break Even rules). Between December 2013 and April 2014 the CFCB will advise clubs of the outcome of their assessment and any punishments. The most serious punishment would be a ban from UEFA competition (with the first ban under for failing the Break Even rules starting in August 2014.

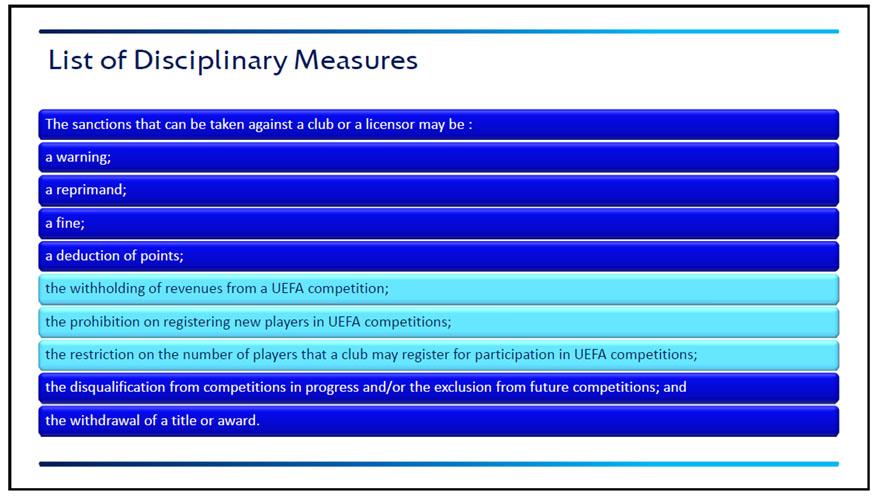

However, there are actually 9 available punishments available:

Reports from UEFA suggest that the three lighter-shaded punishments may be applied to clubs who fail the Break Even test in the very first Monitoring Period. However, as yet, we don’t have any firm information on what punishment will be applied when – it is still entirely possible that PSG for example, will be banned from European competitions in 2014/15.

Amortisation explained

See attached video which explains how players contracts are accounted for - this is an important part of FFP:If a player is sold before the end of their contract, FFP rules require that the difference between their book value at that time and the saleprice needs to be accounted for immediately in the club's accounts. Using the above example, the player signed for £50m on a 5-year contract would have a 'book value' of £20m when he has only two years to run on their contract. If he was then sold for £35m, the club would actually record a £15m profit for that year for FFP purposes (£35m - £20m). Where a club extends a players' contract, the book value at the time the contract was re-negotiated would need to be amortised over the duration of the new contract. These rule applies to all players on a club's books, irrespective of when they were signed (i.e. even if acquired before the commencement of the first FFP Monitoring Period).

If losses are 'trending in the right direction' will a club pass the FFP test?

It is quite common to read journalists state that a club will pass the FFP test if it is 'trending in the right direction' (i.e losses are reducing each year). However this is probably the single biggest misconception about the FFP rules. The confusion is due to something called Annex XI, a rather tortuously worded post-script added to the FFP rules specifically to help clubs comply with FFP in the early years. The most common incorrect beliefs are:

| Incorrect FFP beliefs | |

| 1 | As long as the club is trending in the right direction and the losses are reducing, the FFP test is passed. |

| 2 | The wages of all players signed before 1 June 2010 are excluded from the calculations for every season |

Annex XI is found on the final page (page 87) of the long UEFA document. However I have extracted the relevant paragraphs (although it is hard going for such a short section).

UEFA FFP Wage Exclusion paragraph: Annex XI

Annex XI explained

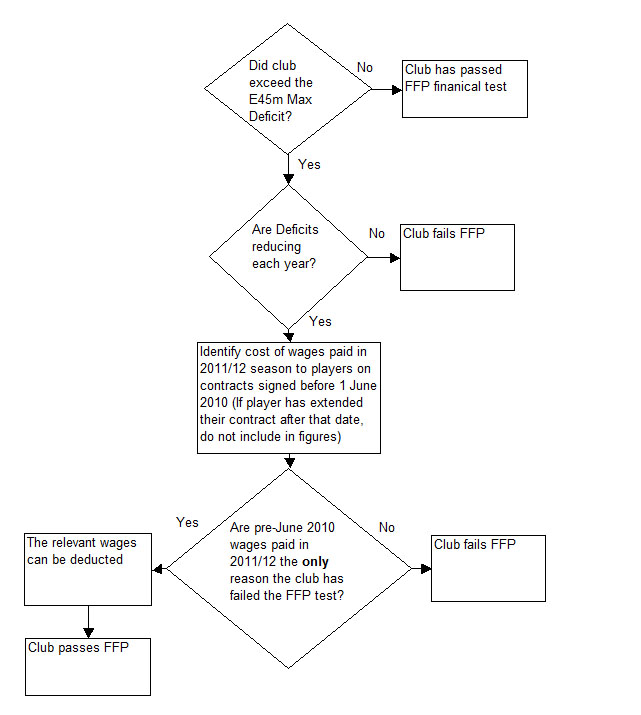

I feel the problematic paragraphs are best explained in my diagram relating to the first Monitoring Period (where the Maximum permitted Break Even Deficit is E45m):

As we can see, if the Break Even Deficits are trending in the right direction, the club can look to exclude wages for long-standing players (i.e. those still on contracts signed before June 2010) to help them pass the test.

Note that this potential exclusion only applies only to the wages for the long-standing players paid during the one season (2011/12). For example, Tevez' wages would have to be included in full for the current 2012/13 season.

So to recap, trending in the right direction, in itself will not be enough to ensure a club passes the FFP test. 'Trending' simply allows a club to deduct wages for long-standing players paid in the season just-finished (2011/12).

This part of the rules is so-often misunderstood that I feel it is worth including some confirmation from top sports Lawyer Daniel Geey @FootballLaw from Twitter late yesterday. On this subject he said:

1..articles make reference to Annex X1 sanction examples

2. Clubs will not be sanctioned IF they have positive cost trend AND would have broken-even had it not been for pre-June '10 contracts.

3. An Annex XI positive trend by itself will not be enough to escape UEFA sanctions.

One final piece on Annex XI. Although the Annex allows the club to exclude wages from players signed before 1 June 2010, there is another reading that could, potentially help clubs; the exclusion could also extend to amortisation as well as wages. However, this is not the generally accepted reading of this and it does not appear to have been UEFA’s intention to exclude both amortisation and wages on the long-standing player

N.B. Where I refer to Max Deficit of E45m in the above diagram, I am referring to the 'Break Even Deficit' - this isn't the same thing as the total loss a club makes as it able to make a number of exclusions from the Break Even calculations (e.g. expenditure on youth and community development).